The fundamental importance of aromas when eating and drinking

Flavour is the most pleasurable and satisfying aspect of food. But when you have a cold, you say you do not “taste” anything. Yet it is not your mouth or taste buds that are congested; it is your nose. Flavours are the characteristics of food and drink we understand least. In terms of aroma perception, we are far from the shark, which, despite its poor vision, can smell its prey more than 10 km away! It is for this reason that some old sailors nicknamed sharks the “swimmer’s nose.”

From a young age, we learn speech and mobility, then reading, listening, and recognizing sounds, looking at and analyzing faces, images, and landscapes. But we are given almost no sensory training about what we encounter 24 hours a day.

The world of aromas is the forgotten sense of the human condition. Historians say we neglected our sense of smell in favour of sight and hearing when we stood upright and developed tricolour vision.

Fortunately, thanks to the leisure society we have built, we are more open than ever to new foods, flavours, and unique aromas. I would go so far as to say that Western countries, particularly Quebec and North America, are at the heart of a powerful sensory awakening. We have come a long way since the end of the Second World War. And because aromas can penetrate the unconscious, unwittingly, for our enjoyment, a new world of fragrances is opening to us.

The aromas of wine, beer or spirits, for example, are surely those that fascinate and challenge the consumer the most, whether they are novices, connoisseurs, or discoverers. The tannins and astringency of wines are notions that are more difficult to grasp. Perfumes tend to be more “sexy,” inviting, festive, inspiring, captivating, intriguing…

Is olfaction subjective?

I often hear that aromas are subjective. Olfaction is no more subjective than hearing! There are no awful scents for perfumers. As proof, all perfumes contain certain repulsive molecules (civet, for example), which, when masterfully dosed, make the bouquet more complex and even magnify the fragrance.

The same goes for music. Have you ever heard a conductor, or a musician say, “I don’t like C major or B flat”? All the notes have their place in a chord, just as in a symphony. Not all of them dominate, but all of them participate in creating “beauty”. The same principle applies to aromatic harmonies and the job of sommeliers.

When you hear a musical composition, it is possible to recognize its composer or the interpreter. When you look at a painting, you can understand the artist’s signature. The same is true when tasting or smelling a great perfume such as Chanel No 5. There is no subjectivity involved. Just as there is a visual signature or a musical signature, there is an aromatic signature.

Why would it be any different for the olfactory sense? As soon as we smell something, we unknowingly identify the atom at the heart of the molecule! When you detect a rotten egg, you recognize the dominant sulphur compound behind the smell, even without having the egg in your hands or your field of vision. Yet this aromatic molecule is not the only one present in a rotten egg.

Your nose determines immediately that the smell comes from a rotten egg. The human nose is a real spectrometer! Trust yourself because subjectivity is more about the personal appreciation of an odour than logical reasoning. Even if I tried to convince you that a Cabernet Franc has a powerful, ultra-refined raspberry scent, you could not appreciate this wine if you hate raspberries. That’s the subjective part.

How many aromas have you smelled in your lifetime?

Have you ever asked yourself this question? From the first taste of breast milk to the vanilla scent of last night’s wine, from the inky odour of a newly printed newspaper to the vaguely herbal scent of shaving cream and the musky smell of your cat’s litter box, how many aromas have you smelled? Seven hundred? Six thousand? Fifty thousand? Even more?

A third of our genes, of our DNA, is dedicated to olfaction. This number is huge! Only the immune system uses as many genes to defend us, lending credence to the theory that smell has been crucial to species selection and human development over the millennia.

The number of aromas that we can smell most often is said to be ten thousand volatile compounds (aromatic molecules, translated into odours or flavours). We often read that the average person could recognize a few thousand smells during his or her life. At the same time, experts, particularly the best noses of perfumery, can detect about ten thousand aromas.

Actually, no one has ever really calculated the smells perceptible by the human nose. Ten thousand aromas to cover all of Earth’s plant and animal kingdoms seems rather low when you think about it. Ten thousand words (or molecules) to name all the aromatic complexity of flowers, aromatic herbs, tree foliage, familiar and exotic fruits, fish, meats, essential oils, wines, beers, brandies, not to mention the reactions of these foods during cooking and their harmony with liquids (wines, beers, etc.).

Add to this the tens of thousands of synthetic aromatic molecules created by man. More than 250 brands are marketed each year in the world of perfumes, each containing 50 to 200 different smells, often with dozens of new aromatic molecules.

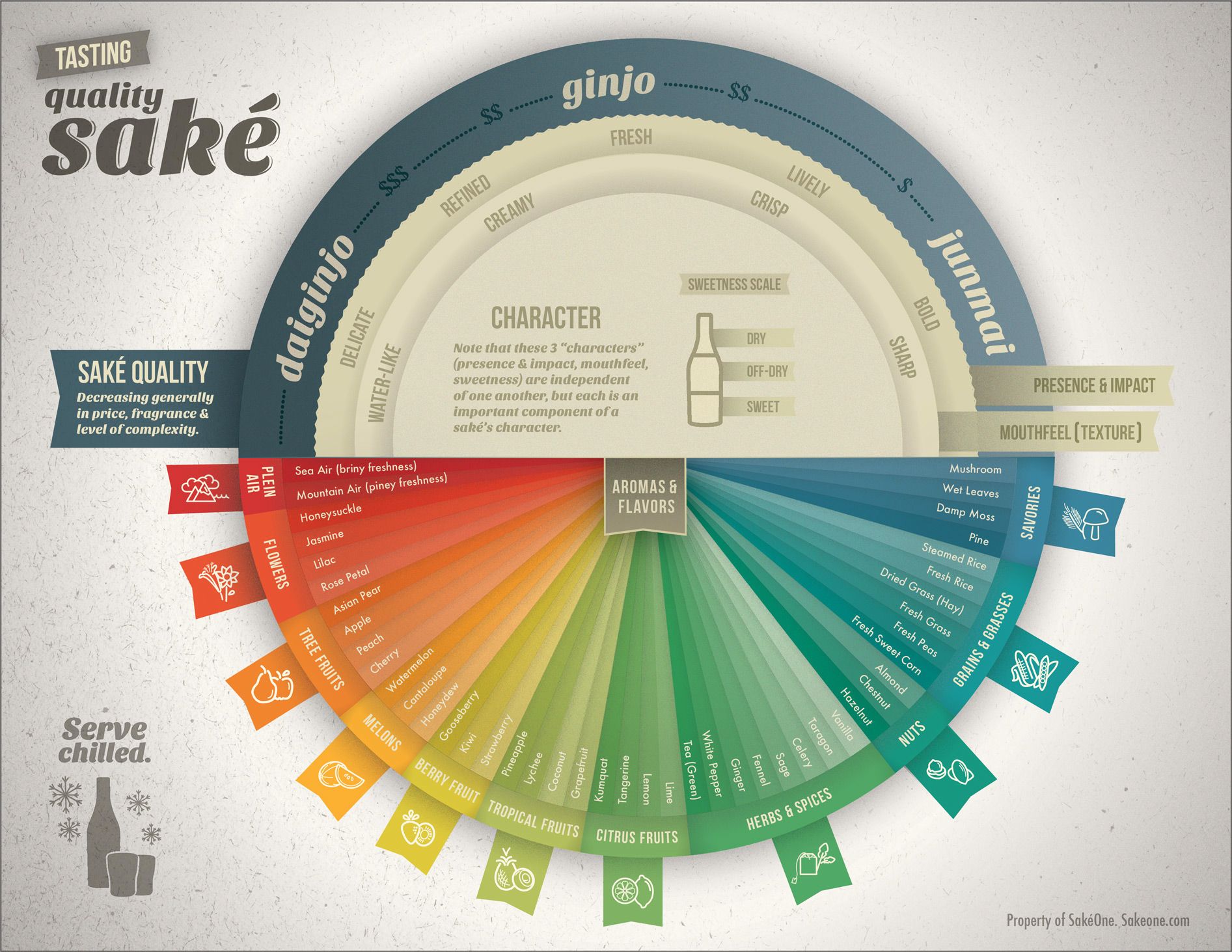

There is a big gap between our real aromatic capacity in everyday life and what we think we can smell. Let’s take the example of the many flavour wheels created to categorize the flavours of certain consumer products.

The beer wheel is said to have been the first to be created in 1970, following the work of the late Danish chemist Morten Christian Meilgaard. This beer wheel had 44 descriptions, divided into 14 categories. Wouldn’t there be more than 44 smells perceived in all the beers of the world? Well, let’s give this wheel a chance!

The wine aroma wheel, created in 1984 by Ann Noble, displays 94 aromatic descriptions (blackcurrant, oak, coconut, pepper, etc.), divided into 12 categories (fruity, woody, animal, etc.) There is a catalogue of the aromatic origin of more than 800 volatile compounds (odorous molecules) in wine. However, we know there are many more fragrances in the different wines made around the world.

There are several other aroma wheels, including one for chocolate (created in Switzerland), honey (Europe), cheese (with only 75 descriptions!), brandy (South Africa) and maple syrup (Quebec). And let’s not forget Mandy Aftel’s list of natural flavours. Each reference is as informative as it is restrictive.

As biophysicist Luca Turin, who specializes in the study of the science of smell and fragrances, says: “There are millions of hypothetical molecules! When you look at all the permutations (carbons multiplied by double bonds, multiplied by isotopic versions of oxygen, methyls attached to propyls attached to ethyls), the aromatic possibilities become stratospheric.”

Aromatic molecules are everywhere!

When you taste a wine and enjoy a meal, you are smelling and eating molecules. When a toast burns in the toaster, the aromatic molecules of charred smoke that enter your nasal cavities warn you. It is the aromatic molecules in your shampoo which provide the scent when you wash your hair, and it smells like melon or fresh herbs. The aromatic molecules emanate from the flowers and circulate freely in the air that reaches your olfactory cilia when you walk into a flower shop and sense the flowery aroma. Molecules are everywhere.

Aromatic molecules are organic compounds responsible for the aromas of what you eat and drink. So too are the scents of flowers and plants, or the foul smells of garbage, old cheese and fish that has gone “bad”.

Olfaction is selective

There are about 400 aromatic molecules in a tomato, yet humans detect only about 15. Coffee has about 800 molecules, but humans only perceive 27, and it only takes 16 of these to recreate the exact smell of coffee.

Therefore, olfaction is selective and directed towards the most dominant molecules that indicate the aromatic profile of foods and liquids. The fact that smell is selective confirms the thesis of my science of aromatic harmonies and sommelier’s art. The basic principle is the aromatic synergy that occurs when dominant molecules of the same family meet between two foods or food and a liquid.

So keep your nose awake!